Why does childhood trauma affect adulthood? The simple answer is how the brain and nervous system encode memory. But like trauma, the simple answer is a bit… complicated.

To understand why childhood trauma can affect adulthood you first need to understand a few things. First, how the brain and nervous system process memory. Second, about the nature of trauma.

Related Reading: Why Understanding What Trauma Does to the Brain Helps you Heal

The Brain and Memory

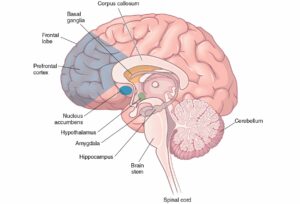

Here’s the brain’s memory roadmap. It starts when sights, sounds, smells, touch, and tastes enter your central nervous system (the brain and nervous system). They do this via sense organs like our eyes, nose, skin, etc.

This information is channeled to a brain structure called the thalamus, whose job is to relay the information simultaneously onto two paths: the “fast” path to the amygdala (the brain’s alarm circuit – I think of it as a smoke detector) and the “slow” path to the pre-frontal cortex (the conscious thinking part of the brain).

This “fast” path to the amygdala is important when you consider trauma. This is because the amygdala, as the body’s fear center (or smoke detector) does several important things. It interprets sensory information, attaches emotional significance, and allows your system to start preparing for potential danger before you even know exactly what the danger is.

This “fast” path to the amygdala is important when you consider trauma. This is because the amygdala, as the body’s fear center (or smoke detector) does several important things. It interprets sensory information, attaches emotional significance, and allows your system to start preparing for potential danger before you even know exactly what the danger is.

For example, think of a time when you were walking and saw a dark, long, thin object on a path. The amygdala determined possible danger and sent signals to the hypothalamus. In turn, the hypothalamus sent signals to your autonomic nervous system (ANS) to prepare for fight of flight. The ANS increased your heart and respiration rates and engaged your leg muscles to slow.

Only a bit later did the prefrontal cortex (remember the “slow” path?) determine with the hippocampus, the brain’s collector of memories, that the object was a stick and not a snake.

Had the cortex determined the object was, in fact, a snake, the nervous system would have propelled a fight or flight or freeze response based on the memories the hippocampus has stored about encounters with snakes. This last part is particularly important when it comes to why childhood trauma affects adulthood.

Childhood Trauma and Memory

In trauma, the brain’s memory system can work a bit too well. Here’s an example.

Eighteen month-old Kate sees a new dog at the park and happily runs to it. The dog, not used to small children, tackles Kate and bites her. The wounds are significant and require surgery. In the hospital waiting room Kate’s parents anxiously await the surgeon to come out. Her grandmother murmurs “It’s lucky Kate is so young – she won’t remember what happened.”

Like the grandmother, we’d all like to believe that Kate won’t remember the dog bite or be affected by it as she grows up. Unfortunately it often doesn’t work that way and here’s why childhood trauma affects adulthood.

The Role of Implicit and Explicit Memory

Kate sees no danger in this new dog because of her positive interactions with the family dog. Specifically, her amygdala so far has only logged good experiences about the mental category of “dog.” Kate doesn’t perceive the possible threat from this dog at the park. This is because at 18 months her hippocampus is only beginning to track, sort, and categorize conscious memories that include thought. These thought-containing memories are called explicit or declarative memories.

Because she lacks an explicit memory that includes the thought “some dogs are dangerous,” Kate just goes with the happy impulse to run to the dog. That is, Kate acts only on procedural memory, also called implicit memory, which relies on instinctual or conditioned responses and emotional associations (“Doggy!”).

How Kate responds to strange dogs in the future depends on how well her parents and other adults helped her nervous system contain and process this event. If this outside help was insufficient or not well-matched to Kate’s nervous system, she likely will have a fearful response to strange dogs in the future. This is driven by her procedural memory, even though she won’t have a conscious memory of the dog attack.

Now if Kate’s hippocampus is online and fully functioning (that happens sometime after 18 months, give or take), the brain will more likely have explicit memories that help inform how the body should react to threat in the here and now.

How Kate’s body “should” respond in the present is driven by how it responded the last time to survive the threat. So in the future Kate may freeze when she encounters a strange dog – just as her system froze during the attack. This will happen even though present circumstances may suggest that fighting or fleeing might be more appropriate responses. This is a key reason why childhood trauma affects adulthood.

Related Reading: 3 Ways Childhood Trauma Can Affect Your Adult Relationships

The Nature of Trauma

So now that you have a sense as to how the brain and nervous system form memory, let’s look at trauma. There are many ways to define trauma, but two of them really stand out for me.

The Cognitive Definition

In this definition, trauma is something that is horrific, terrifying, or threatening that a person doesn’t have an adequate frame of reference with which to make sense of it.

A good example is the experience of September 11, 2001 in the United States. While the coordinated attack on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, and the related downing of United Flight 93 in a field in Pennsylvania were truly horrific events, they were not psychological traumas for the vast majority of the American people.

Why? Because in the days and weeks following the attack, people across America who were not directly affected by the events talked about it incessantly and collectively created a frame of reference for the event. Commercial aircraft used as missiles is terrorism. To be safe we need to defend against this threat that is called terrorism. (To be clear, people at Ground Zero or those with pre-existing related traumas did rightly experience 9/11 as trauma.)

Now consider that the nature of childhood, particularly early childhood. By definition childhood is a time of not having an adequate frame of reference to make sense of the world. When things go as nature designed, parents, caregivers, and other adults help the child to make sense of his or her experience, creating frames of reference.

For example, think of a 2 year-old’s birthday party. The cake, blowing out the candles, singing the happy birthday song, the gifts – all are accompanied by smiles and laughter – and by explanation. Jack is 2 years-old today – yay! Let’s sing for the birthday boy! It’s your special day – happy birthday Jack!

All those experiences and explanations work to contain emotional experience. They also build a frame of reference – a mental category of “birthday” for the child.

But in trauma, the event is generally not a happy one – indeed it is highly emotional and threatening. And those critical clues and all important explanations are not there or are inadequate.

An Example

Eight year-old Rachel hears the harsh sounds of her parents fighting despite her closed bedroom door. The next day after breakfast, Rachel’s parents tell her they have decided to divorce. They tell her “nothing will change, but mom will be living in a new place.” Overcome by their own emotions, they share little else. Rachel asks to be excused and goes to her bedroom sure that her parents’ decision to divorce is all her fault.

This painful experience mars Rachel’s mental category of “marriage.” The explanations provided by her mom and dad were inadequate to help Rachel make sense of the event. Lacking an adequate frame of reference, Rachel’s brain comes to a default meaning: it’s my fault.

These default meanings are always negative and about the self. It’s as though the brain lays a floor with the worst possible meaning – perhaps so that any other meaning determined later becomes possible. These default meanings are another important reason why childhood trauma affects adulthood.

The Somatic (Body) Definition

The second definition of trauma addresses the body aspect of trauma. Here trauma is defined as when something threatening that overwhelms the body’s ability to cope or defend itself in the moment. Whatever that something is, it comes too fast, or comes too soon, or it’s too much, or it’s too… you fill in the blank.

For example, a car accident happens too fast and overwhelms the body’s instinctive responses to defend and protect itself. The body wants to get away from the threat, but is trapped. Consequently the body’s defensive and protective responses don’t get to complete.

Instead the thwarted survival energy of these motor patterns remains trapped in the nervous system, and, according to Peter Levine, the developer of Somatic Experiencing, underlies the symptoms of PTSD.

To illustrate, let’s go back to the example of little Rachel. Because the divorce threatens Rachel’s world, that is, her intact family and home, the event taps into survival physiology. Her parents, overwhelmed by their own emotions, fall short with helping Rachel. Specifically, they don’t sufficiently help her nervous system contain and process the activation that the threat to survival is producing.

Short of sufficient containment and “digestion” of survival threat, the energy of the thwarted fight/fight/freeze or submit responses lives as trauma in her nervous system. As Rachel becomes an adult and enters relationships, this survival energy of childhood trauma still simmers underneath, silently affecting adulthood. It exerts an often subconscious warning when relationships start to feel intimate: get away – it’s not safe!

Related Reading: Can Childhood Trauma Cause Anxiety? Yes, Here’s How

Clues that Childhood Trauma May be Affecting You Now

The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study and other research shows the strong link between childhood trauma and illness, whether physiological and psychological, in adulthood. If you’re uncertain if you had childhood trauma, you might consider taking the brief ACEs screening.

Certain mental health issues and patterns are clues that childhood trauma might be affecting you in adulthood. According to mental health professionals, here are common ones that often have a childhood trauma link:

• Chronic Anxiety or Depression

• PTSD

• Personality Disorders such as Borderline or Narcissitic

• Dissociative Disorders

• Substance Abuse or Dependence

• Process addictions or compulsivities such as eating disorders, sexual addiction, etc.

• Autoimmune Disorders

• Unremitting patterns in relationships or other aspects of life such as work

• Chronic sleep disturbances

• Problems with anger management

• Persistent feelings of shame

• Self-harm, cutting, self-mutilation

What to Do If You Are Affected by Childhood Trauma

Childhood trauma resolution generally can’t be done on your own. Ignoring the trauma and other forms of overriding will usually just further entrench symptoms. Nor is childhood trauma something that responds very well to regular talk therapy.

Research has shown that body-based therapies are the most helpful in resolving childhood trauma that may be affecting you in adulthood. Find a therapist trained in one of these therapies that specifically address trauma:

• EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing)

• Somatic Experiencing (the touch element of SE can be particularly helpful for early, non-verbal childhood trauma)

• Sensorimotor Psychotherapy

• Somatic Trauma Therapy (the work of Babette Rothschild, MSW)

So if you still have questions about why does childhood trauma affects adulthood, my Chicago area practice specializes in the treatment of trauma, as well as addiction. We recognize the importance of body-based therapy for trauma, we offer EMDR, Somatic Experiencing, Yoga Therapy, Dance Movement Therapy, and more. Please reach out to us at our Glen Ellyn, Chicago (Jefferson Park), or Sycamore offices.

Rhonda Kelloway, LCSW, SEP